Failure as an Option

Stories in Conflict

Cell and gene therapy can cure cancer. Simply put, cells are removed from a patient, reengineered, and returned to the body as medicine. The body then fights the cancer on its own.

Studies show very high success rates. However, the therapy is complex, the process lacks transparency and is prone to errors due to manual intervention. Each drug has to be produced individually, which requires a lot of resources: time, staff, infrastructure – in other words, money.

As a result, the therapy is only accessible through clinical trials – if a patient is already terminally ill and failure is legally unproblematic – or if the patient is wealthy enough to afford it out of his own pocket.

Daniela Buchmayr wants to change that.

At this time, Daniela is director of innovation and application development at a company that also supplies technology to the pharmaceutical industry. She proposes researching a solution that would automate and miniaturize the process of cell and gene therapy, and make it measurable and traceable using sensors. Daniela developes a comprehensive strategy and presents it to the board of directors. There she receives recognition: the idea seems compelling and could work. Nevertheless, it will never come to life. Too long term. Too expensive.

Disappointed and frustrated, Daniela leaves the company and faunds the start-up Sarcura with researchers from various fields. Together, module by module, they are developing a technology that could be groundbreaking for cancer treatment. The goal: to make this promising therapy available to everyone who needs it.

The start-up is quickly finding supporters – even though the first prototype is still several years away. This is not only due to the founders’ good network: In conversations with investors, I often hear that Daniela’s background and personality were particularly convincing.

Her story gets a lot of things right: it authentically communicates what Sarcura is all about. And it is an impressive example of efficient storytelling.

Cause and Effect

In a workshop with students, I try to explore the reasons. We ask ourselves why Daniela’s story motivates people to support her. The students’ answers vary:

- It is a true story. It has more power than any marketing.

- The vision appeals to investors who want to support projects with impact. Even rich people want to do good.

- Cancer can affect anyone.

- The therapy already exists. It’s just a matter of making it accessible. That seems feasible.

- The story communicates Daniela’s experience. Most start-ups first have to establish their standing and learn a lot of skills. Daniela already has them.

- The idea that only a few can afford the treatment is unfair and triggers something in us.

- It confirms our prejudice against corporations that put short-term profit above the long-term common good. When something confirms our opinion, we listen.

- The story doesn’t have a happy ending yet. Daniela needs us.

The most banal answer does not require any arguments at all:

How could you not support such a startup if you have the means to do so?

When the student notices my smile, he adds almost defiantly: “But that’s the truth!” And of course he’s right. There is no other way to put into words what good stories do to us.

Ben is dying

If we want to understand the effect of good stories, it makes sense to look at the findings of Paul Zac. He is a neuroeconomist – a researcher who applies the principles of neuroscience to the field of economics. In his book “Why Inspiring Stories Make us React: The Neuroscience of the Narrative,” he describes a study in which two identically composed test groups were each shown a video of a father and his son.

The overarching theme is childhood cancer. The volunteers are paid for their time – and also have the option of donating a portion of that payment to an NGO that supports families with children suffering from cancer.

The first video shows a father and his son on a sunny day at the zoo. A tumour is mentioned and the boy has a bald head. Otherwise, the story is unremarkable and consists of a simple sequence of banal situations.

The second video shows a father who is devastated. He speaks in a broken voice, while his son Ben bobs happily back and forth on the swing in the background.

The father talks about how difficult it is to play with Ben. Because Ben is so happy, so wonderful. But he knows something that Ben doesn't: that Ben is dying.

We follow the father as he struggles day by day to be there for Ben without allowing himself to be overwhelmed by his grief. And we witness his transformation into a man who learns to accept the inevitable and cherish every moment he has with his son.

Until Ben dies.

The pyramidal structure of Gustav Freytag's drama (1863)

Credit: Florian Hämmerle

The Neuroscience of the Narrative

While the first group experiences a film without a story arc, the second sees a short story based on the structure of a classic drama by Gustav Freytag. The narrative thrives on a central conflict that inevitably leads to a catastrophe. We know that. And yet it holds our attention to the end – as we want to know how the father deals with the tragedy.

The difference in the willingness to donate is remarkable: while only individuals from the first group donate, half of the second group sacrifice a large part of their compensation to the aforementioned NGO.

This is completely voluntary, which is impressive. After all, the financial incentive is the main motivation for most people to take part in such a study in the first place.

Paul Zac sees the reason for this change in behaviour in neurochemistry: blood tests show that cortisol levels in the brain rise after just a few scenes. If the story holds their attention long enough, the test subjects enter a state of immersion and oxytocin is released.

Cortisol is a stress hormone. It makes our heart beat faster, accelerates our breathing rate and sharpens our attention and information processing. Oxytocin, on the other hand, is known as the bonding or cuddle hormone; among other things, it has a stress-reducing effect and controls our mental well-being.

The University of Zurich has investigated the connection between oxytocin and trust in other people and found that the neurotransmitter promotes empathy – and therefore our ability to empathise with others and to feel with them. And Paul Zac comes to a similar conclusion: he describes oxytocin as “the moral molecule” – in other words, as a trigger for moral behaviour.

Oxytocin can not only change our attitude towards a person or a topic. It can even influence our social behaviour.

To give stories this impact, they need strong narratives. They need dramaturgy and therefore conflict, says Paul Zac.

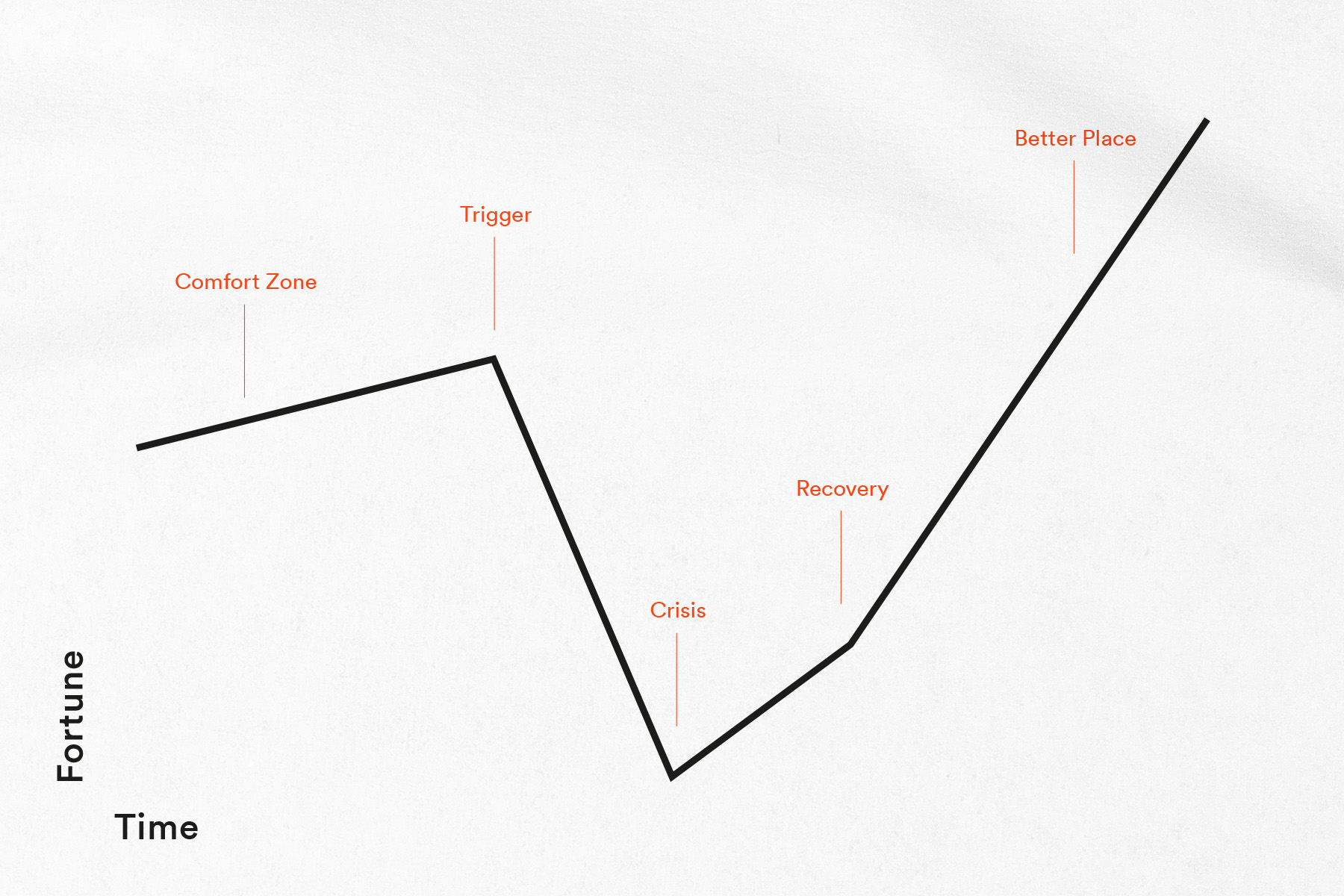

Kurt Vonnegut's plot arc "Man in a Hole" is a simple blueprint for dramatic narratives.

Credit: Florian Hämmerle

Marketing in Conflict

Good stories therefore attract attention and build trust – even at the neurochemical level. Good branding has a similar goal: attracting attention to messages while at the same time building trust that they are meant seriously. If these two aspects are at odds with each other, it becomes difficult to achieve the goals of communication – to influence behaviour.

It is therefore not surprising that storytelling has become a buzzword in the communications industry. This is despite the fact that this industry often finds it particularly difficult to tell stories in the first place. In many marketing departments, the view still prevails that a brand should not be associated with anything negative. The result is a shortcut: instead of addressing problems and thus creating relevance, many simply jump to the solution. This is somewhat paradoxical: after all, what is the point of a solution if the problem doesn’t even exist?

When you want to motivate, persuade, or be remembered, start with a story of human struggle and eventual triumph. It will capture people’s hearts – by first attracting their brains.

Paul Zac

In my workshops, we experiment with story arcs to reinforce narratives. I use a worksheet based on Kurt Vonnegut’s narrative arc “Man in a Hole” – one of a total of six plots that the American author identified in literature and film.

Its structure is outlined relatively simply:

- Comfort Zone: Not necessarily a bad place. And yet something is missing. The protagonist is wasting his potential.

- Trigger: A misfortune, self-inflicted or caused by others. Something throws the protagonist off course.

- Crisis: A low point. In the darkness, the protagonist finds or learns something of great value.

- Recovery: A new beginning, the resurgence begins. The protagonist uses what he has learnt in his darkest hour.

- Better Place: A happy ending. Matured (and aged), our protagonist forms a new, better world.

So we deal with long-suppressed student experiences and reassemble them. And not everyone feels comfortable with that. So I leave it up to the participants to decide who wants to talk and who doesn’t. What follows is remarkable:

When the first participant starts to speak, the room goes completely silent.

He tells us that he used to work in a company that claimed to be innovative. How he was ridiculed and repeatedly ran into walls. But that he believes in his ideas and wants to prove with his start-up that they work. Another admits that this is already his second start-up. He had completely missed the market – a mistake that would not happen to him again. And a third says that she has lost a loved one. And therefore wants to work for a start-up dedicated to the early detection of diseases.

Of course, not all stories are so impressive. And it takes courage to talk about the low points of our lives. After all, we are showing a vulnerable side of ourselves. But these stories also makes us accessible. And they give the other person an insight into our personality and our ability to respond to defeat and grow from it.

The short stories not only tell us who we are. But also how we got to be who we are. What drives us and what defines us. How we deal with crises and what we learn from them. And in some cases, what strategies we have developed to avoid defeat in the future.

This creates trust that goes far beyond professional expertise.

The messages of Sarcura in one picture: Challenge, appeal, strategy.

Failure as an Option

But back to Daniela’s story: it contains several elements of compelling storytelling – a great injustice, a feisty protagonist, a tragic twist, a sad low point, a courageous new beginning, competent comrades-in-arms, a clear strategy and a great vision.

The central conflict – failure in the eyes of her employer – makes Daniela’s frustration and drive palpable. It conveys the image of a strong-willed and resilient personality who takes a personal risk to realise an idea. And it follows a dramaturgy that creates suspense and leaves the ending open.

Through her story, an investor not only learns essential information about Daniela’s background and qualification, but also gets a sense of how she will react to obstacles: She will fight for what she believes in. This creates a sense of security and trust – at least on an emotional level.

So it makes sense that we take her story as the starting point for the brand essence. It becomes Sarcura’s narrative anchor. The claim “Bring it to life” is a logical culmination and is deliberately aimed at partners and investors. After all, the first step is to find supporters who want to contribute to Daniela’s great vision.

Partners and investors become part of the story. And (with a bit of luck) help it get the happy ending she deserves.

I, for one, am excited to see how the story continues. And I’m glad to be part of this exciting journey.

To be continued, then. I’m sure of it.

Weblinks

Why Inspiring Stories Make Us React: The Neuroscience of Narrative by Paul Zac

Trust, Morality – and Oxytocin? Ted Talk by Paul Zac

Wenn Hormone Vertrauen wecken by Robert Nickl, Universität Zürich (German)

The emotional arcs of stories are dominated by six classic shapes Wissenschaftliche Publikation

Freytag’s Pyramid: Examples of the 5 Elements for this Classic Narrative Structure by Joe Bunting

Literature

The Moral Molecule: How Trust Works by Paul Zac

The Moral Molecule: The Source of Love and Prosperity Audiobook, Paul Zac

Florian Hämmerle

Author

Cover Picture

Lisa Vlasenko

Photography

lisavlasenko.com