Silence

An Experiment

I capture many of my observations in small fragments of text. Those are mostly single words, sometimes loose sentences. But sometimes, they become a little more: short stories in which I experiment with words, narrative structures or characters. “The Extra” is the first chapter of “Silence”, a short story I wrote on the train from Graz to Vienna. It is unfinished and will probably remain so – a curious attempt to apply the model of archetypes to writing and thus draw characters that are comprehensible and tangible in only a few sentences.

The text was initially written in German. I have done the best I can to translate it into English.

The Extra

It was Monday morning and it was raining. The lobby was already crowded and K. had taken his usual place. Close to the entrance, on the hard barred bench – where he had a good view and looked inconspicuous enough not to attract too much attention. The notebook was open on his thigh and he was writing down the date of the day.

There was something magical about this place. A voiceless murmur echoed in the imposing hall of Viennas Central Station. The mood of the light changed fluidly with every rain cloud that moved across the sky. This was where beginnings and endings met, a creative space where stories were constantly being reinvented and waiting to be told.

It was K.'s favourite retreat. Here he felt safe.

And among all these strangers, a little less alone.

The day began as usual. Doro opened the grate of her flower stand with a metallic screech and paused briefly to give K. a scolding look. She didn’t like him, which wasn’t hard to tell. In truth, she was creeped out by the fact that he was constantly watching her and taking notes. She had confronted him several times, but apart from a meaningless look, she never got a reaction.

The rumours about his silence were in full swing. The staff made up new ones every day: some thought he was a foreigner who simply did not understand. Others said he was obsessed with the flower lady and was stalking her. A lovesick freak, they said. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. But it certainly flattered Doro and softened her mood at least a little.

The truth, as usual, was mundane. K. couldn’t talk. Unlike others, he had no voice. He hadn’t spoken a word to anyone since he was about five years old. And the psychologists were at odds whether he couldn’t or simply wouldn’t. K. did not know it either.

He liked the idea of remaining silent in protest.

A wordless rebellion against the people who, he felt, talked all the time but had so incredibly little to say.

But K. was also plagued by melancholy. He loved language, the sound of words. Silence isolated him. Like an extra, he was at the centre of life but couldn’t take part. He longed for normality, for a real life. Along with all its trivial episodes.

Episodes he witnessed in abundance at this station. Most days he would sit for hours, almost motionless, listening and watching. His pencil scratched over the pages he always carried with him. Same as today.

By now the rush hour had begun and the voiceless murmur became more urgent. People streamed into the hall, shaking out their umbrellas or throwing a soaked newspaper into the rubbish that had just served as a rain shelter. Among them, K. recognised one or two familiar faces; friends, as he called them. To each of them he dedicated a page of his book.

There was the young man in the business suit – he called him Ben. Like every day, Ben rushed to the office to fulfil someone else’s dream. Young and ambitious, he hadn’t yet realised that work could impossibly be everything. Chasing status and recognition, he nipped at the heels of the old with the vigour of his youth. Constantly torn between having and needing, he fully ignored his exhaustion.

It was a rare moment when Ben paused briefly, glanced at the stations display and rolled back his shirt to study his chronometer. His train was late; it was a quarter to eight, and the silence made him uneasy.

And there was Mei Linh, dragging her four-year-old behind her as usual at this time of day. The little boy, who was getting heavier by the day, kicked furiously as he tried to free his arm from his mother’s grip. He simply didn’t understand why he was pointing at all sorts of delicacies, yet his mother made no effort to buy him what he was pointing at. Mei Linh – was she Chinese? Vietnamese? Japanese? – placed him somewhat roughly on one of the large plastic elephants, on which he rocked lethargically back and forth for just one euro. There were days when she quite liked her son. Today was none of them.

Ashamed of the thought, she took a deep breath, walked into the wholefood shop and bought herself a clean conscience.

The two of them were actors in a play that they didn’t even know about. In his desperation, K. created his own world. He observed and noted, strung together sentence after sentence, attaching meaning to each word, inventing plots, roles and names for his actors as he saw fit. In his mind, he sat in the shadows of a brightly lit stage, surrounded by an entourage. He directed as a conductor, in secret, and remained a stranger to his performers. And so he invented and he shaped his characters with the care and love of a father who never forgot to be gentle or strict. Each day, he added a new tile to the mosaic of his play.

Doro, for example, took up several pages in his book. Perhaps because she was an open book herself. Her flower stall was at the far end of the hall. On the sign was an endearing “Doroflores”, probably a mixture of the Latin word for flowers and the owner’s first name, Dolores Hubmann.

The words "Say it through flowers" paid tribute to a marketing consultant who had promised Mrs Hubmann an increase in sales – for a small fee, of course.

Doro had been married for thirty years to a failure who earned far too little, forcing her to sell this grass every day. Yet she never left him. Fearing change, she preferred to live a life without culmination. She leaned lovelessly and listlessly against her stall, reluctantly watering her source of income and spending most of her time forming all sorts of opinions about others. For example, the old man who slowly but surely made his way to her stall was a thorn in her side even before he made his request.

She replied loudly and rudely, which was all too understandable: after all, her counterpart was old and probably senile. Her stern features sank to the floor when, after half a minute, Alfred – the working title – still didn’t know what he wanted to buy. Her question as to whether she could help him sounded like a threat. Her posture sank on the counter, her index finger hammering impatiently on the wood.

The old man didn’t notice. He was deep in thought. For in a few hours he would be reunited with the love of his youth. He didn’t care about the withered flower child. How long they hadn’t seen each other! Fifty-three years! Would she still recognise him? His lips hinted at a smile and his big hands reached for a bunch of flowers whose name he didn’t know. He was nervous, his hands trembling even more than usual. What a fool he was.

What would his son say? How unreasonable.

At his age! Was he too old to love?

A colourful spot caught K.’s eye. Lena, a teenager from the suburbs, had struck her pose on the platform. She was sucking lasciviously on a cigarette. Lena was just fifteen, her hair bleached to the roots and her face painted with a passion for symmetry. It reminded K. of an abstract work of art that, with few strokes but all the more colour, suggested a face similar to that of a sparrow. Combined with her petite stature, she was about as attractive as a peppermint candy, but apparently unaware of that. She kept shifting her stance from one leg to the other, drawing the smoke from her cigarette through her teeth. She was nervous. Like so many times before, she had to explain to her annoying elders where she had been over the weekend.

Like every Monday morning, she drove home tired and tipsy, made the usual excuses and lied herself into bed.

Meanwhile, Doro had pulled herself up with a jolt. A young, well-dressed man, a potential Kevin, had entered her stall and inquired about a bunch of red roses. Her voice quavered and suddenly broke into an eager singsong. She hurried to choose the most beautiful flowers for the handsome young man who had to be successful and thus in a hurry. Her wrinkles had shifted from vertical to horizontal. As the young man left the stall, her gaze followed him, somewhat dreamily, before returning to Alfred and darkening again. She held out a bunch of wilted daffodils and asked him with a demanding voice if he had been looking for them.

K. liked his new character, opened a blank page and wrote a name on it: Alfred, 74, was a retired shipbuilder, former layabout and flatterer. He was from the country, where people still knew their neighbours, said hello to the bus driver and spoke one of those charming dialects. He had plucked up the courage to travel to the big city. Lonely as he was, he finally wanted to do what he didn’t have much time for: her name was Martha, she was beautiful and she was missing to his happiness.

"Hello."

A child’s annoying speech impediment snapped him out of his game. Startled, he dropped the pencil and a six-year-old girl giggled in amusement. “You’re funny,” she squealed, saying something K. had never heard before. Confused, he raised one eyebrow – always the left one, he realised – and noticed with unease that the child was coming closer and closer. Curious, she met his gaze, smiled kindly and then stepped back as if she understood.

K. studied the little creature thoroughly. It was quite small, had a sloppy ponytail and was dressed in pink, as the general public would probably expect. In the girl’s hand was a brightly coloured stuffed animal that K. could not identify as any known species. It happily bobbed on its heels back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, and tried again, tilting its head:

"Hello. I am Emily. And you?"

K. could only shrug his shoulders. He would have liked to say something. But at the same time, he preferred to remain silent. Because the thought of his voice … Well, did he have any? He didn’t know. So he looked around for help and spotted the supposed mother in the middle of a queue in front of the tobacco machine. Obviously, she had been standing there for a while, looking worriedly at her child, who was talking to a stranger without permission. She seemed torn between her place in the queue and the welfare of her daughter. She didn’t want to give up either.

Emily made no move to go over to her mother, who was now waving her arms energetically. Instead, she looked straight into K’s face. Her mouth twisted into a question that she did not ask. Instead she put her finger up her nose.

She had to think.

Story abandoned.

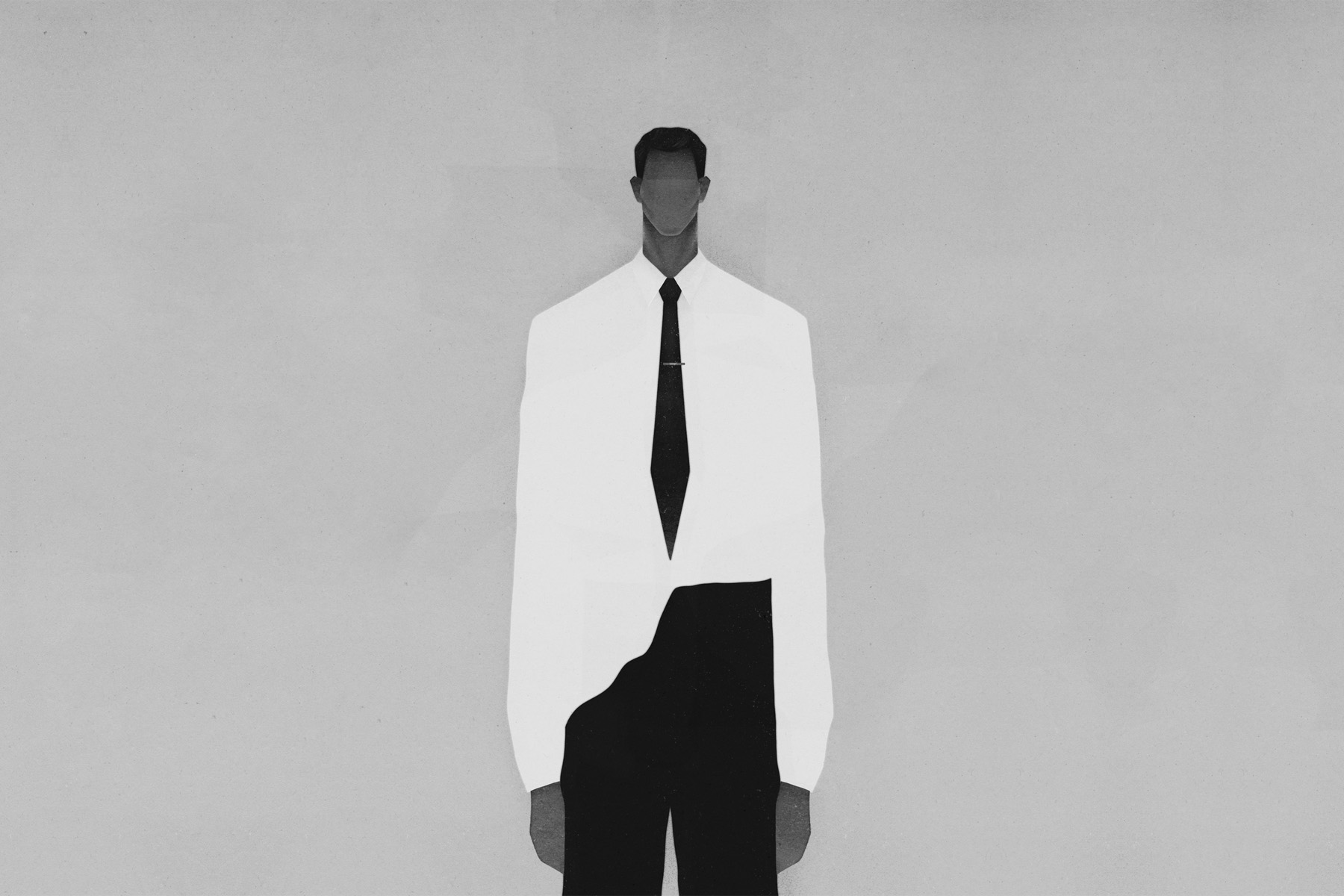

Valeriya Simantovskaya is an artist and illustrator who lives and works in Yerevan, Armenia. Valeriya has a degree in architecture, but started working with illustration during her studies. For about 8 years now she has been exploring human nature – especially the human body – and the relationships between people and social phenomena in her work. She experiments with textures and compositions. Her limited colour palette and simple geometric shapes give her works a minimalist character that leaves room for interpretation. A portrait of the artist and a selection of her works can be found here.

Florian Hämmerle

Author

Valeriya Simantovskaya

Illustration

behance