Human Needs in Branding

A Roadmap to Purpose

Why am I actually doing this? This thought visits us all from time to time, for some it is even a permanent visitor. If we lack a goal, a clear direction according to which we structure our lives, we lose our footing. We waver back and forth between different extremes and find no balance among all the competing needs, desires and expectations.

We find the motif of the search for meaning wherever there are stories.

Brands also tell stories. And stories need a hero. C.G. Jung’s archetypes form the ideal bridge between storytelling and a brand’s identity. They stand for intuitively understandable behaviour, create personality on the outside and identification on the inside. As symbols, they embody what makes us human: our individual search for safety or esteem, for belonging or self-realisation.

Marketing without a system for managing meaning is analogous to ancient navigators trying to find port in treacherous seas or a starless night. What they need is an enduring and reliable compass – a fixed place that illuminates both where they are and where the must go.

"The Hero and the Outlaw"

Margaret Mark / Carol S. Person

What basic human needs influence us in our search for meaning? And how can this knowledge help us to lead brands out of disorientation? Part 1 of the article addresses these questions.

Part 2 then takes a closer look at the principle of archetypes according to C. G. Jung and explains how they can provide an answer to the question of “why” that Simon Sinek outlined in his Golden Circle. This part also provides an overview of Carol Pearsons and Margaret Marks model of archetypal branding.

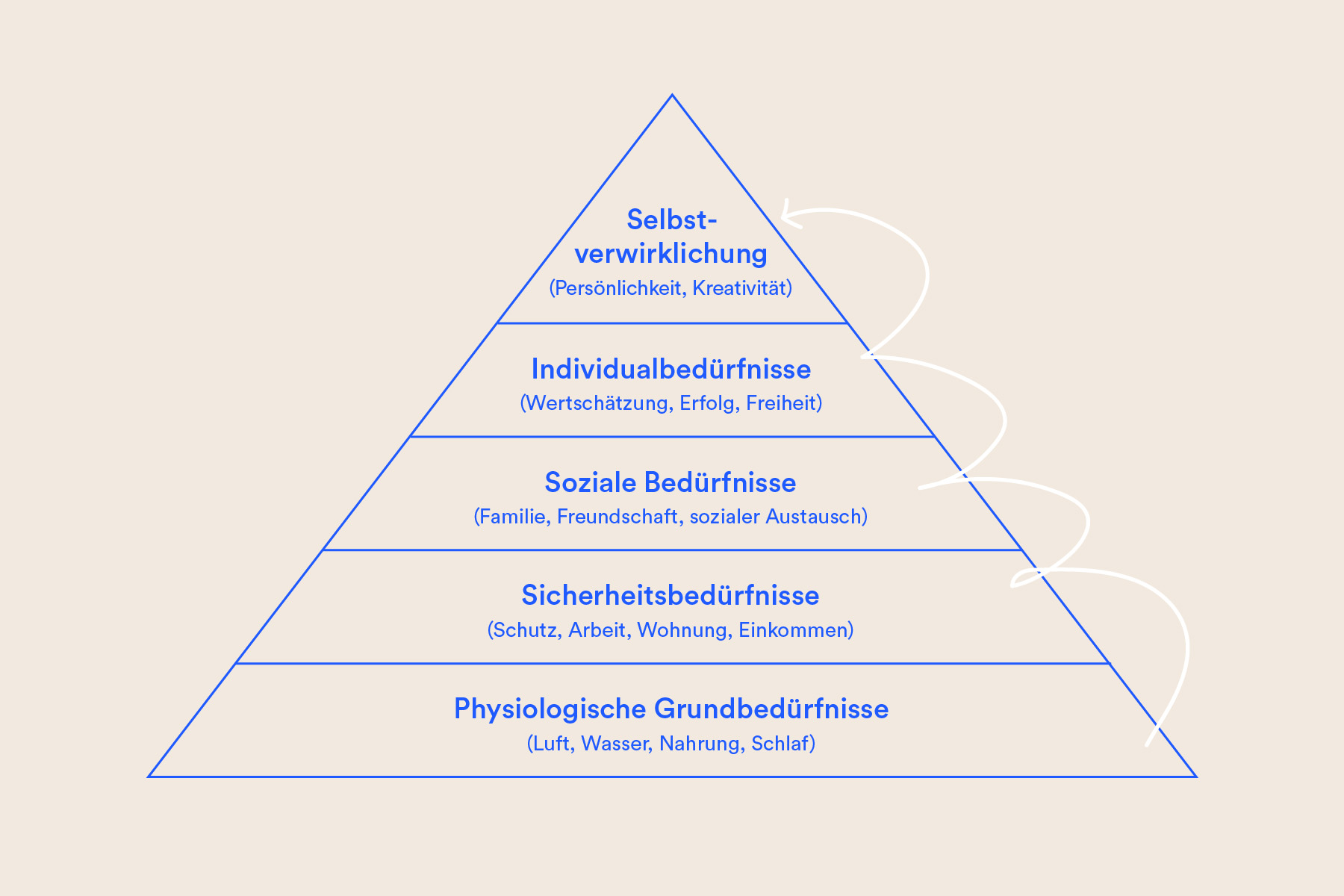

Maslow's pyramid of needs has a strictly hierarchical structure.

Design: Andrea Holzner

Falafel before self-discovery:

The Maslow pyramid of needs

A cloud of buttery fried onions drifts out of the window of an open apartment block, a gust of wind carries a wave of falafel scent past, while a fruit stand around the corner smells invitingly of melon. Anyone who has ever travelled through the city famished knows how the feeling of hunger can overshadow all other impressions and needs.

We associate this hierarchy of needs with no one more than Abraham Maslow, the 20th century American psychologist. Maslow’s well-known pyramid of needs is based on a hierarchical structure: He states that some of the needs have a higher priority than others. He divides the needs into a pyramid with 5 subsequent levels.

While walking hungrily past the falafel stand is of course a privileged example of hunger, it shows well that our basic physiological needs must first be satisfied in order to have capacity to question the meaningfulness of our own work or belonging to a certain group. We can only move on to the next stage once our most basic needs have been met.

Satisfied desire ceases to be desire. The organism is dominated by unsatisfied needs that determine behaviour.

"Motivation and Personality"

Abraham Maslow

In practice, however, needs are not a rigid framework. The transitions between the different levels are often fluid and different needs exist at the same time. Maslow himself subsequently corrected the interpretation of his theory:

“So far, our theoretical discussion may have given the impression that these five sets of needs are somehow related to each other in a successive all-or-none relationship. We have formulated it like this: ‘When one need is fulfilled, another arises’. This statement could create the false impression that one need must be 100 per cent fulfilled before the next one arises.”

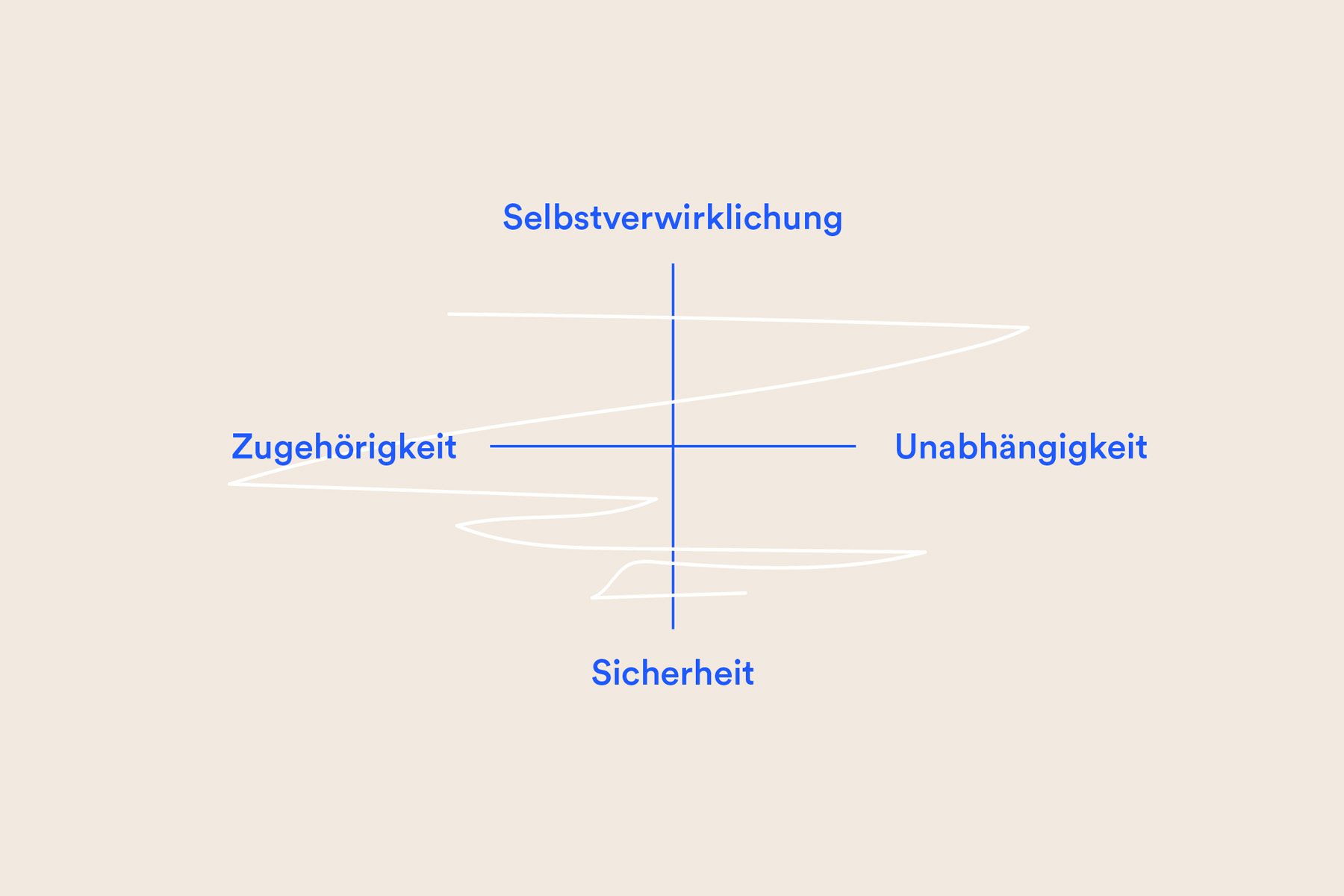

Pearson and Mark reinterpret Maslow's model in the form of opposing poles.

Design: Andrea Holzner

Always in conflict:

The Mark and Pearson model

Margaret Mark and Carol S. Pearson developed another model to explain basic human needs. In their book “The Hero and the Outlaw”, they present a scheme that characterises needs on the basis of poles. On the one hand, belonging and independence, and on the other, safety and self-realisation.

Life requires constant negotiation along these poles. When we sacrifice one end of one of these continua to the other end, there is a tendency in the psyche to seek balance.

"The Hero and the Outlaw"

Margaret Mark / Carol S. Person

Whilst some people are clearly attracted to certain poles, for most it is a process of constant weighing up. Desires compete, change, are satisfied or remain unfulfilled.

Between the Shire and adventure

Bilbo Baggins from J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Hobbit” is a character who is a good example of this dichotomy. One morning, Bilbo’s tranquil life is unexpectedly disturbed by the wizard Gandalf, who wants to recruit him for an adventurous mission. But Bilbo hesitates. He is torn between the fear of leaving the safety of the familiar Shire behind and the newly awakened ambition to prove himself.

It was a beautiful morning when an old man knocked on Bilbo's door. "We don't want any adventures here, thank you," he dismissed the uninvited visitor. "Anyway, what's your name?" - "I am Gandalf," he replied. And then it dawned on Bilbo: the adventure had already begun.

"The Hobbit"

J.R.R. Tolkien

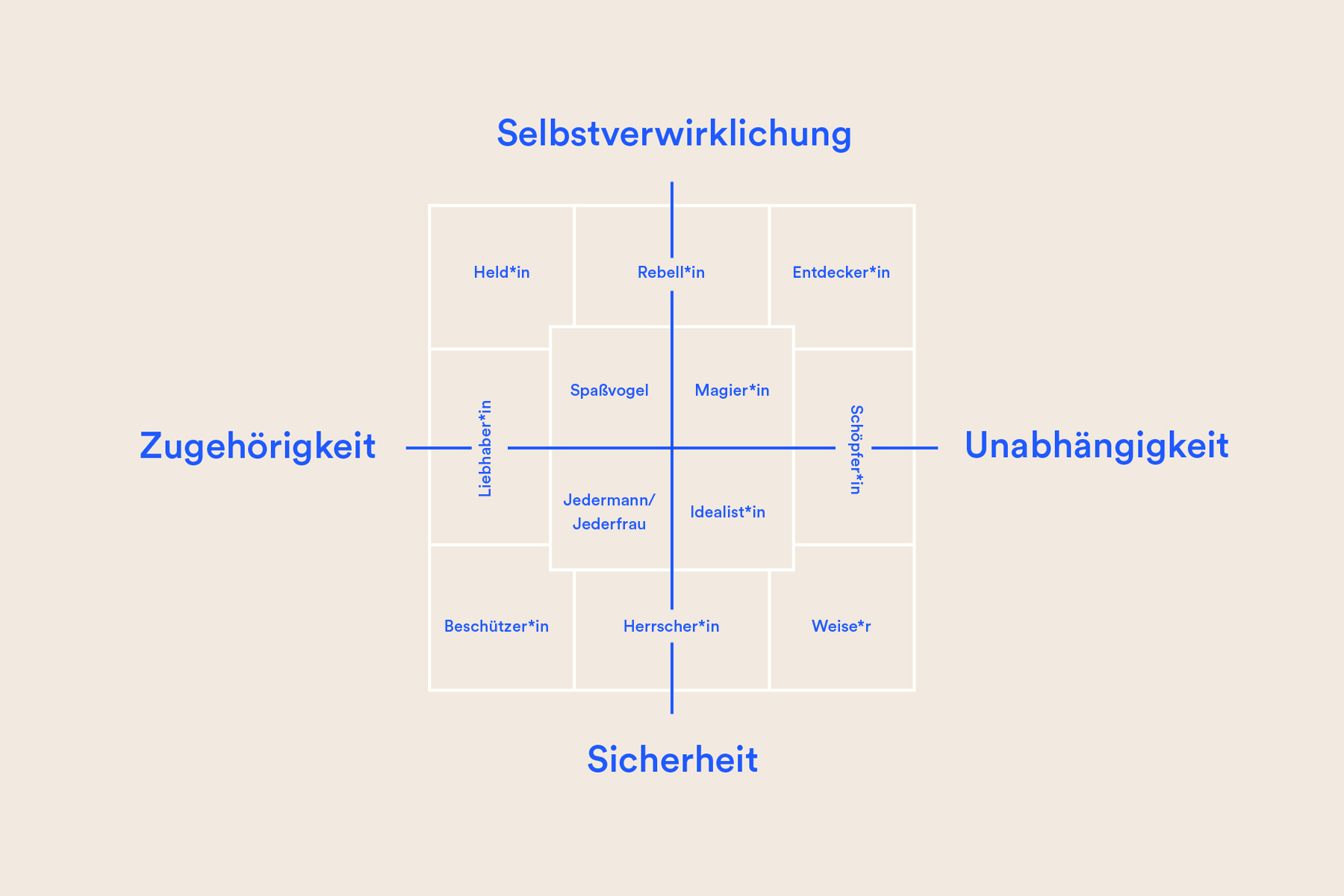

Bilbo’s example shows that the localisation between the poles of need is not rigid. Even if the call of adventure is stronger in the end, he always longs to return to his familiar cave in moments of crisis.

So instead of placing a character in the system of the two axes, you can allow them a little room for manoeuvre. This variance could be represented, for example, by locating the archetypes in areas.

Archetypical Positioning according to "Markenbrand, Zeitschrift für Markenstrategie"

Source: Hochschule Neu-Ulm, 6/18

A gutty decision

Even if potential buyers rarely have to choose between an adventure with a horde of dwarves or the tranquil life at home, their everyday lives are also characterised by a multitude of decisions. And just like Bilbo, they make most of them based on their gut instinct.

With just a few clicks of the mouse, countless companies with the same focus can be compared and weighed up against each other. In 2021 alone, there were over 87,000 new trade mark applications in Germany (source: DPMA). In the end, however, the decision is not only based on objective criteria, but also on (unconscious) emotions and needs. Which provider can we identify with the most? Who best addresses our needs? A cautious, anxious person will always choose the company that gives them the most reassurance.

Successful brand communication must therefore be aware of the desires and emotional needs that drive its target group.

But recognising vulnerability and desire also brings responsibility. Where is the line between a fair response to a need and the exploitation of people's fears?

This is not an easy question to answer in theory, but in reality the demarcation is even more complex. There is no simple answer. Questioning yourself and being open to criticism is therefore an essential part of good and honest branding. After all, communication is there to reach customers and start a conversation – it’s the actual service that has to deliver.

Turning many into four:

The basic needs in detail

While these models look at people’s desires from different angles, they essentially describe the same four needs. Only their exact names and the way they are presented in relation to each other may vary.

- Stability/Safety

Focus: Safety, protection, order, emotional stability and well-being, health and financial security; desire: “I am safe” - Community/Belonging

Focus on human interaction: needs for love and belonging (friendships, family); desire: physical and emotional intimacy: “I am loved” and “I belong” - Esteem/Individuality

Focus on self-worth: status, success, recognition; desire: to define and increase one’s own value: “I am valuable” - Self-Realisation/Purpose

Focus on growth/potential: education, development of skills, creativity, talent; desire: to leave one’s mark, find meaning: “I make a difference”

Even if we still can’t confidently answer the initial question “Why am I doing this?”, perhaps it’s enough to ask the right question in the first place. Sometimes our intuition can take us further than rational thought ever could.

In the next part of this article, we will look at how to use intuition in the branding process, and where C.G. Jung’s archetypes come into play.